Albert William Ketèlbey 1875 - 1959

Contrary to claims that the name Ketèlbey was a pseudonym, the composer was indeed born Albert William Ketèlbey (without the accent) on 9th August 1875 at 41 Alma Street, Aston Manor, Birmingham, son of George, an engraver, and Sarah, whose maiden name was by coincidence also Aston. The house no longer exists, the area having been cleared in the 1960s to make way for blocks of flats and garages, and for the Newtown shopping centre.

Piano lessons must have started at an early age, for we next find the eleven-year- old Albert at the piano of Worcester Town Hall, playing his own composition grandly titled Sonata, to an audience including Edward Elgar. On his own admission, he was a reluctant pianist, but was inspired to composition by a passion for the daughter of the organist of the church choir in which he sang.

Such was his talent, that by the age of thirteen he won a scholarship to Trinity College of Music in London, an institution with which he was associated for many years, first as a pupil, later as an examiner. Although trying his hand at other instruments, including organ, flute, oboe, clarinet and cello, his first instrument remained the piano, with composition taking an ever-increasing role.

While still at the College, Ketèlbey managed to have many short pieces published. The more serious appeared under his real name, but he also produced a string of salon pieces and mandoline music under the splendid pseudonym of "Raoul Clifford". There was even a song called A dream of glory which had the credits "the music by G. Villa, organ part by Raoul Clifford." Villa Road and Clifford Street are both thoroughfares close to the Alma Street of his birth.

On leaving the college, Ketèlbey’s work as an examiner enabled him to include some of his own educational pieces on the Trinity College examination syllabus. His main employment was now with two publishing firms. At Chappell's he made reductions of orchestral music for solo piano, while at Hammond's he did the reverse, and orchestrated classics of the piano repertoire for the ever-increasing market of the salon orchestra. This hack-work may have been tedious, but the experience was invaluable in moulding the composer's fluent writing for both piano and orchestra. Hammond also handled most of his early compositions, not only piano pieces, but a large number of songs and even the light opera The Wonder Worker, which had been produced at the Grand Theatre, Fulham, in 1900.

Hammond's was a small firm, unable to furnish publications with the elegant pictorial covers of the larger publishing houses. While still using Hammond for most of his lighter output, Ketèlbey tried to interest more famous publishers in his more serious works. Odd pieces were published by Novello & Co., Ascherberg, Hopwood & Crew, and the American firm Theodore Presser Co.

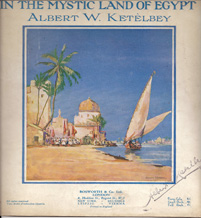

The breakthrough into the quality market of full colour pictorial covers did not come until1915, when within a space of weeks; Larway issued In a Monastery Garden and Ascherberg Tangled Tunes. By this time, Ketèlbey was obviously well-known in musical circles, for the artist who drew the cover for Tangled Tunes wittily depicts the composer himself as a sorcerer concocting a mixture of runes in a large cauldron.

In 1907 he had taken a job as "impresario" with the Columbia Record Company. In true showbiz fashion, his conducting career was launched when the regular conductor was indisposed, and over the years he rose to become the company's musical director. During the First World War, he also held the same post in revues promoted by André Charlot, including Ye Gods (1916), Flora (1918) and The Officers' Mess (1918). In such productions, music needed to be direct, instantly setting a scene. Similar qualities were needed in the new market of music for the silent cinema, and the composer duly produced collections of brief mood-setting pieces. In later years, at the peak of his popularity, he was able to recycle some of these fragments as concert pieces.

Significantly, one of his collections of cinema music was published by Bosworth. After the First World War, this firm became Ketèlbey’s major publisher. The balance of the market had changed, with light music now being recorded almost exclusively in orchestral versions. 50 for the first time, Ketèlbey’s music was published simultaneously in two versions, piano and orchestral. The former were distinguished with eye-catching covers, and were printed by Bosworth in London.

The orchestral parts were printed by the firm's Leipzig branch. Arrangements for other performing media, such as military and brass bands, violin with piano, and organ, followed later, with the work being delegated to professional arrangers.

Bosworth's lavished much care over the production of the music. The printing was spacious, mistakes rare, and the product was marketed with a high-profile advertising campaign, taking the prime pages at the centre of the journal Musical Opinion."

We believe the One Great Bright Spot at the present time is the wonderful success of Albert Ketèlbey dance sensations." (1920)"

The world's three greatest successes, featured by all the English, American and continental orchestras..." (1923)"

Broadcast performances of Ketèlbey actually advertised for one year numbered 1580" (1933)

In the space of ten years, Ketèlbey became the most successful composer in the land. With foresight he had joined as early as 1918 the Performing Right Society, the body which gathered revenue from performances of members' works. The Society had a complicated classification system for distributing its income, to the disadvantage of the more popular composers. Basically, "serious" composers and publishers received more than those operating at the lighter end of the market. The matter came to a head in 1926, when Ketèlbey actually resigned because his cinema music published by Bosworth was classified below that of other publishers, even though it was being performed more frequently. The matter was only resolved by a review of the whole policy, and by 1929 he was proclaimed in the "Performing Right Gazette" as "Britain's greatest living composer", on the basis of number of performances of his works. That he could gain so much popularity irked less successful composers, and there were frequent signs of professional jealousy. The critic Ariel, writing in Musical Opinion, jibed at his "inexpensive pseudo-orientalism", and when challenged, declared that In a Persian Market is bad music, without skill or convincing quality of any kind."

A third setback during this period was the Polly case. In 1922 the Kingsway Theatre revived the eighteenth-century ballad opera Polly, which was a sequel to the well-known Beggar's Opera. The only music in the original score consists of songs with just melody and bass line, with no harmonies, orchestrations or instrumental introductions. The composer Frederic Austin was invited to arrange the music for the normal twentieth-century forces. The show was a hit, and a selection from Austin's musical arrangement was recorded by HMV. Ketèlbey was still working as musical director for the rival recording company Columbia, and they sought to cash in on Polly's success by issuing a selection of their own before the HMV recording was released. The Columbia version was of course arranged by Ketèlbey, who claimed to have worked from the original sources. Nevertheless, the finished product was close enough to Austin's for a writ to be issued for breach of copyright. The case of Austin v. Columbia Record Company came before Mr Justice Astbury, and the list of witnesses ran like a "Who's Who in music" - Ernest Newman, Sir Hugh Percy Allen and Geoffrey Shaw were called for Austin, while Sir Frederick Bridge, Hubert Bath, Sir Frederick Cowen, Sir Dan Godfrey, Hamilton Harty and George Clutsam testified for Ketèlbey. Both plaintiff and defendant sang musical examples to support their case. The judgement went against Columbia and Ketèlbey, but the last word must surely go to the aging Sir Frederick Bridge: "Austin and Ketèlbey are good musicians who have no reason to be fighting over this... What an awful bore this is!"

By the end of the 1920s, Ketèlbey’s success as a composer was great enough for him to be able to give up his post at Columbia, and devote himself to composition. Each year he would do a tour of seaside resorts to give special Ketèlbey concerts, which would include his latest novelties. Among these were several pieces for piano with orchestra, and he revived his career as pianist to play the solo part in such items as The Clock and the Oresden Figures and Caprice Pianistique (recorded on Marco Polo 8.223442)

The annual tours ceased soon after the Second World War. Tastes were changing, and the composer's powers waning. Apart from a commission to write The Adventurers Overture for the 1945 National Brass Band Competition, little of interest was produced. The Ketèlbey’s income from performing rights dropped from £3493 in 1940 to £2906in 1950, a massive decrease when wartime inflation is taken into consideration. He even found that his works were being neglected by the BBC. A broadcast festival of light music in 1949 failed to include any of his music, an omission which caused him to complain bitterly that this was a public insult by the BBC.

In truth, his music lacked novelty. Of the handful of works published in the post- war years, most were reworkings of old material, although the composer attempted to disguise the origins. Thus a song called Kilmoren was in fact a revision of Kildoran, which had been the tenor's lead number in The Wonder Worker fifty years earlier. Even the recent Adventurers Overture was refashioned as an orchestral piece.

When the composer died in December 1959, his will was couched in terms to dissuade his widow Mabel from allowing access to his private papers, thus closing the most direct avenue for research into his music. In any case, a flood at his house in Cowes in the winter of 1947 had probably already destroyed the bulk of his manuscripts. The apparent loss of the Hammond archives after the firm was bought up, coupled with the far-from-complete holdings of the British Library, has meant that our knowledge of his music is limited. Several published works have not survived in any public collection. Many earlier pieces lack publication dates, and can only be placed in chronological order by cross-referencing plate numbers with individually dated copies. The absence of manuscripts and diaries leaves us only able to speculate about the pre-publication history of the music.

For a concise history of Albert William Ketelbey you should read "From The Sanctuary Of His Heart" Reflections on the life of the Birmingham composer By John Sant. -> (Link to book review)